Keith Haring: ‘Art is for everybody’

Reading time: 5 mins

Raised in rural Kutztown, Pennsylvania, Keith Haring (1958 – 1990) rose to prominence in the 1980s. By blurring the boundaries between street art and conventional exhibition spaces, he went on to become one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century. Today, he is still celebrated for his political activism, his philanthropy, and his creation of an artistic language that still resonates with diverse audiences. We explore Haring’s innovative artistic practice and how the man who championed ‘art for everybody’ rocketed to international fame.

Early influences

A child of the 1960s, Keith Haring was influenced by his amateur illustrator father, and the cartoons he saw on television by Walt Disney and the Looney Tunes characters. When he finished school in 1976, he went on to study commercial art in the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh. The experience was short-lived. Haring read Robert Henri’s The Art Spirit (1923) and it had a profound effect upon him. The book encourages artists to engage in an interactive artistic practice, and it dawned on the aspiring artist that he wasn’t interested in commercial advertising.

Instead, he wanted to make art that was accessible and socially relevant. Describing his school experience in an interview, Haring reflected that ‘The people I met seemed really unhappy; they said that they were only doing it for a job while they did their own art on the side. But, in reality, that was never the case: their own art was lost. So, I quit the school.’

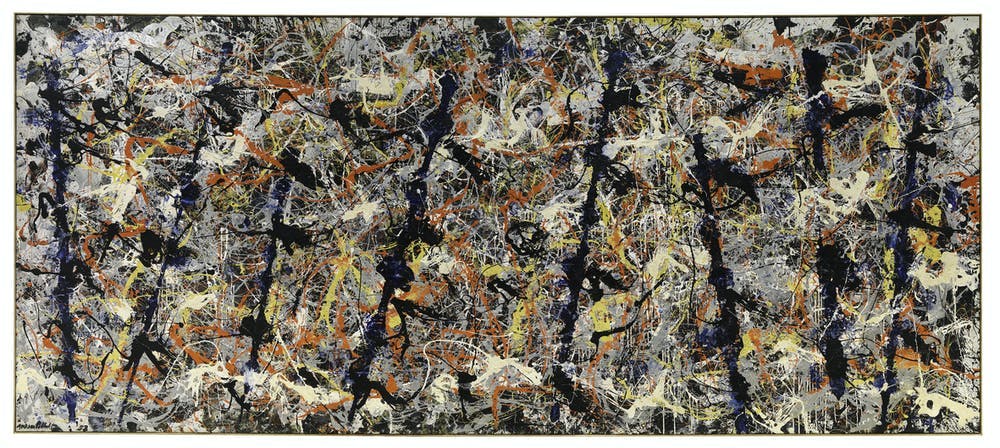

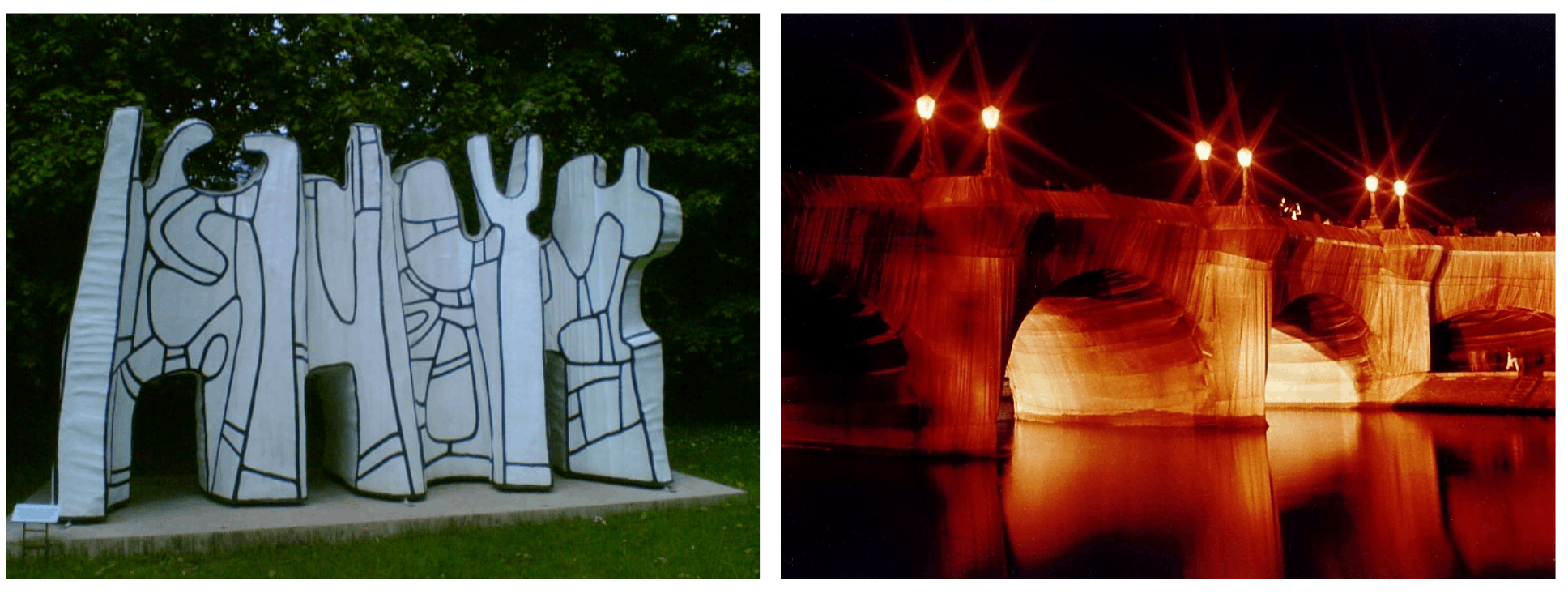

Dropping out after just two terms, Haring took the leap and studied art independently; borrowing books from The University of Pittsburgh Library. He managed to support himself by landing a job at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, and it was there that he first encountered artistic giants that would influence him for years to come. He discovered the illustrative directness of Jean Dubuffet’s ‘raw art’, the seemingly spontaneous execution of Jackson Pollock’s action paintings, and the dense compositions produced by Mark Tobey.

Increasingly seduced by the concept of scale, Haring’s work grew bigger and more impactful. Influenced by a lecture he attended by the Bulgarian sculptor Christo – who enlightened him to the potential of large-scale works like Running Fence and Pont Neuf wrapped (below) – Haring endorsed the belief that ‘art could reach all kinds of people, as opposed to the traditional view, which has art as this elitist thing.’ Such views gave Haring the confidence to transform his small abstract drawings into monumental works.

A lucky break

Haring’s break came when an artist cancelled an exhibition at Pittsburgh Arts and Crafts Center and he was able to step in at the last minute. The event marked the first rung of the ladder of the ambitious young artist’s creative career, giving him the confidence he needed for the next big move: relocating to New York City. ‘From that time, I knew I wasn’t going to be satisfied with Pittsburgh anymore or the life I was living there. I had started sleeping with men… I decided to make a major break. New York was the only place to go.’

‘I saw this empty black panel where an advertisement was supposed to go. I immediately realised that this was the perfect place to draw.’

Keith Haring

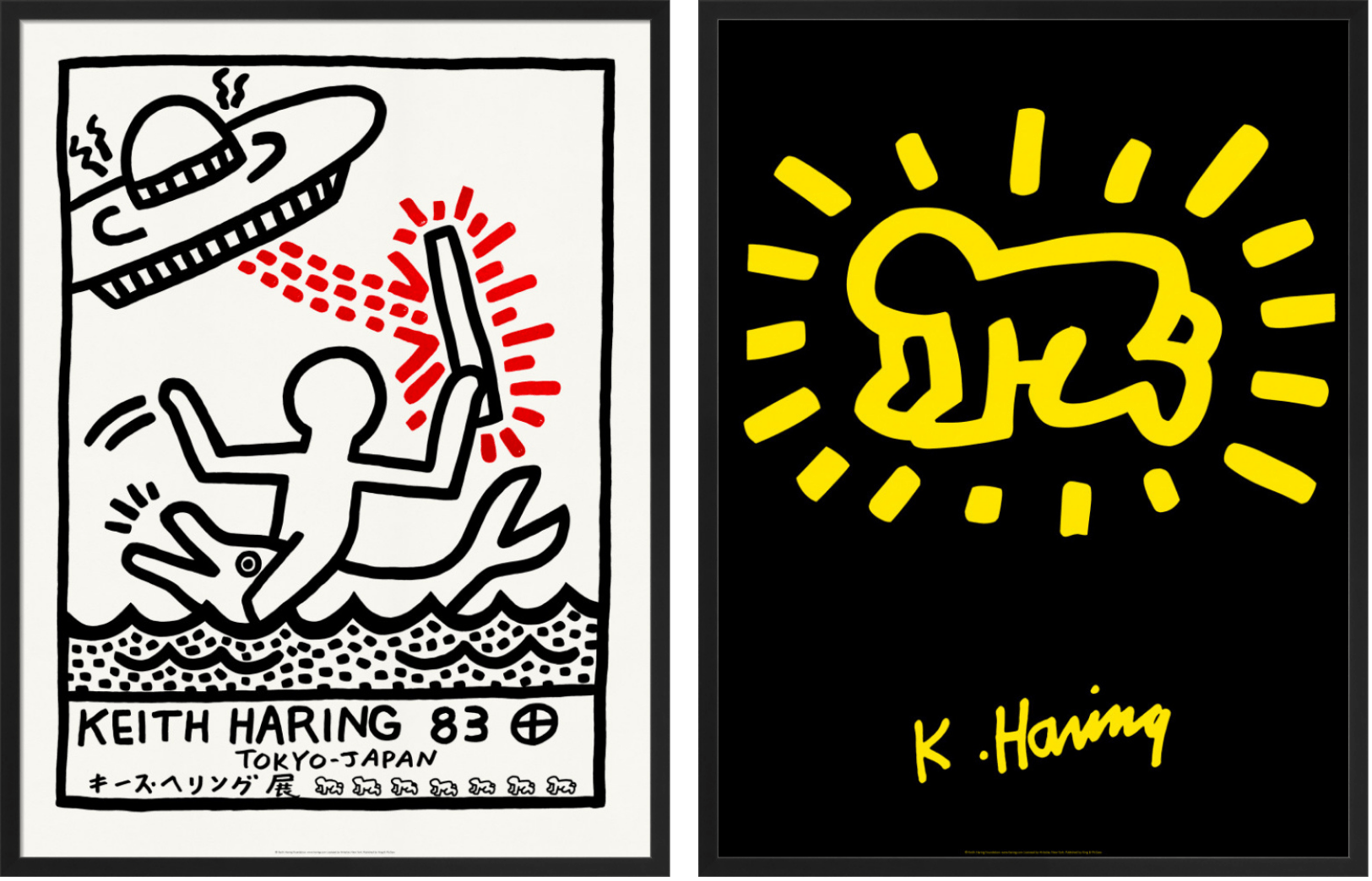

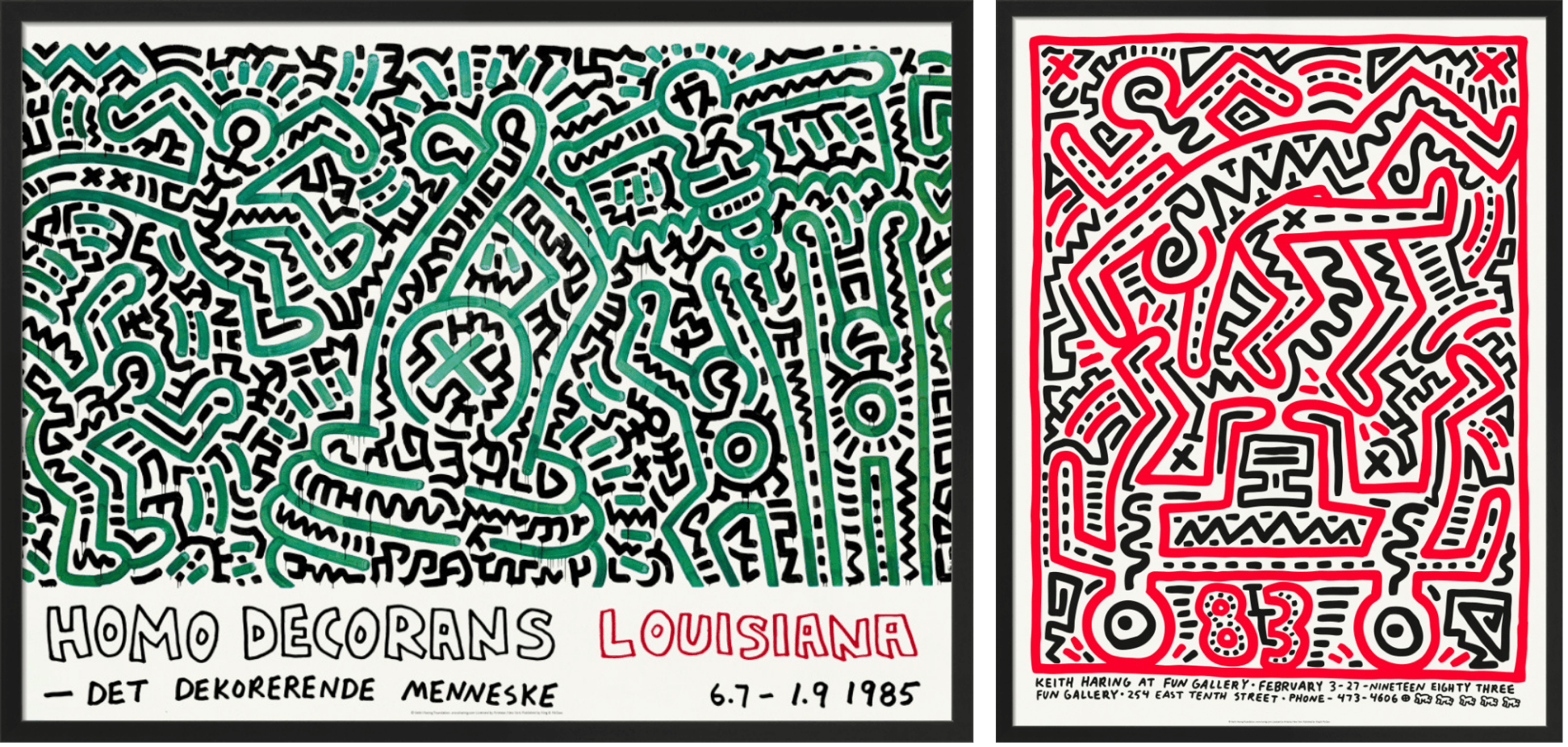

Studying at The School of Visual Arts in New York in 1978, Haring found his unique expressive vocabulary. Barking dogs, flying saucers, radiant crawling babies, and large hearts soon became integral ingredients to his idiosyncratic iconography. Keen for others to see his work, he hung his drawings in the School’s hallways and repurposed disused advertising spaces on the subway to experiment with his style.

Talking to journalist David Sheff for Rolling Stone in 1989, Haring explained that he ‘saw this empty black panel where an advertisement was supposed to go. I immediately realised that this was the perfect place to draw [...] I kept seeing more and more of these black spaces, and I drew on them whenever I saw one.’ Over time, drawing with chalk, he transformed these public spaces into his own creative lab where he could develop and make new iterations of his characteristically large figures, bold outlines, and striking lettering.

Haring thrived on the public performance of his work. Drawing in the New York subway enabled him to receive live feedback from people from all walks of society. Speaking to David Sheff, he reflected that the conversations with the public were one of ‘the main things that kept me going so long – the participation of the people that were watching me and the kinds of comments and questions and observations that were coming from every range of person you could imagine, from little kids to old ladies to art historians [...] Art lives through the imaginations of the people who are seeing it. Without that contact, there is no art.’

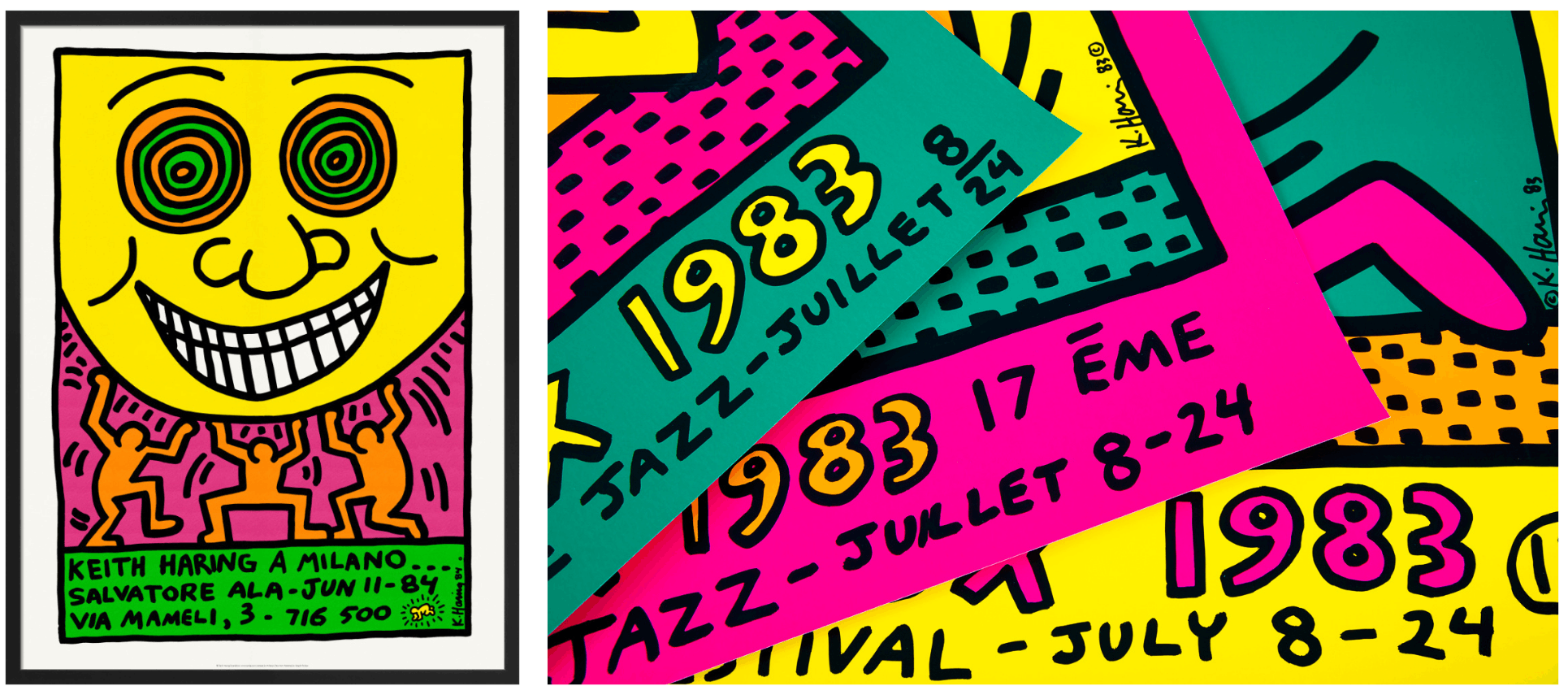

With growing recognition of his work and more money to finance his ambitions, Haring embraced new opportunities. In 1985, keen to make his work available to more diverse audiences (beyond the museum elite), he rented a ground floor space on Lafayette Street on lower Broadway in New York. Initially he used it as an exhibition space for ‘Rain Dance’, a group show curated with sales proceeds benefiting African famine relief.

One year later, the space became his famous ‘Pop Shop’, where he expanded his artistic output to produce affordable t-shirts, buttons, magnets, postcards, watches, and apparel. And, since they were more democratic – and cheaper to produce – he also began designing public posters. Using a black marker, he initially made outlines of his designs and added tracing paper overlays with Pantone colour indicators. He opted for offset printing because it produced a similar, high-quality finish to silkscreen printing.

Art for social causes

Acutely aware of the exploitative practices of large commercial sponsors, Haring embraced charity work and increasingly used his art to highlight pertinent social causes. Working on a voluntary basis, he organised workshops with children and produced large-scale murals at New York’s Woodhull Hospital.

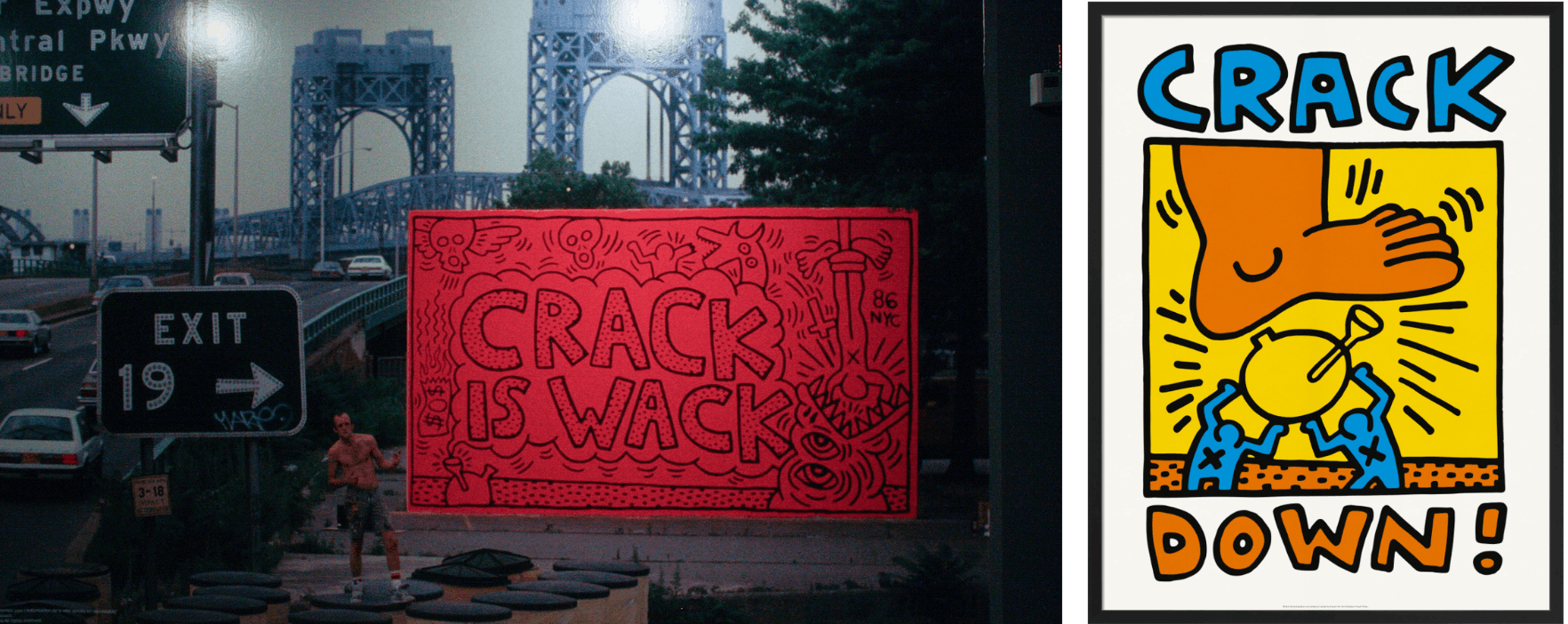

Drug use was also rampant and Haring produced a mural called ‘Crack is Wack’ in 1986. Much cheaper and dangerously more addictive than its powdered counterpart, crack cocaine became popular in poor and working-class neighbourhoods. In a bid to warn people about the dangers of the drug, Haring strategically placed his ‘Crack is Wack’ mural on the Harlem River Drive in East Harlem. The mural also held personal significance to Haring as his studio assistant and friend, ‘Benny’, took an overdose of the potent drug. Crack is Wack therefore became a mural to honour Haring’s lost friend.

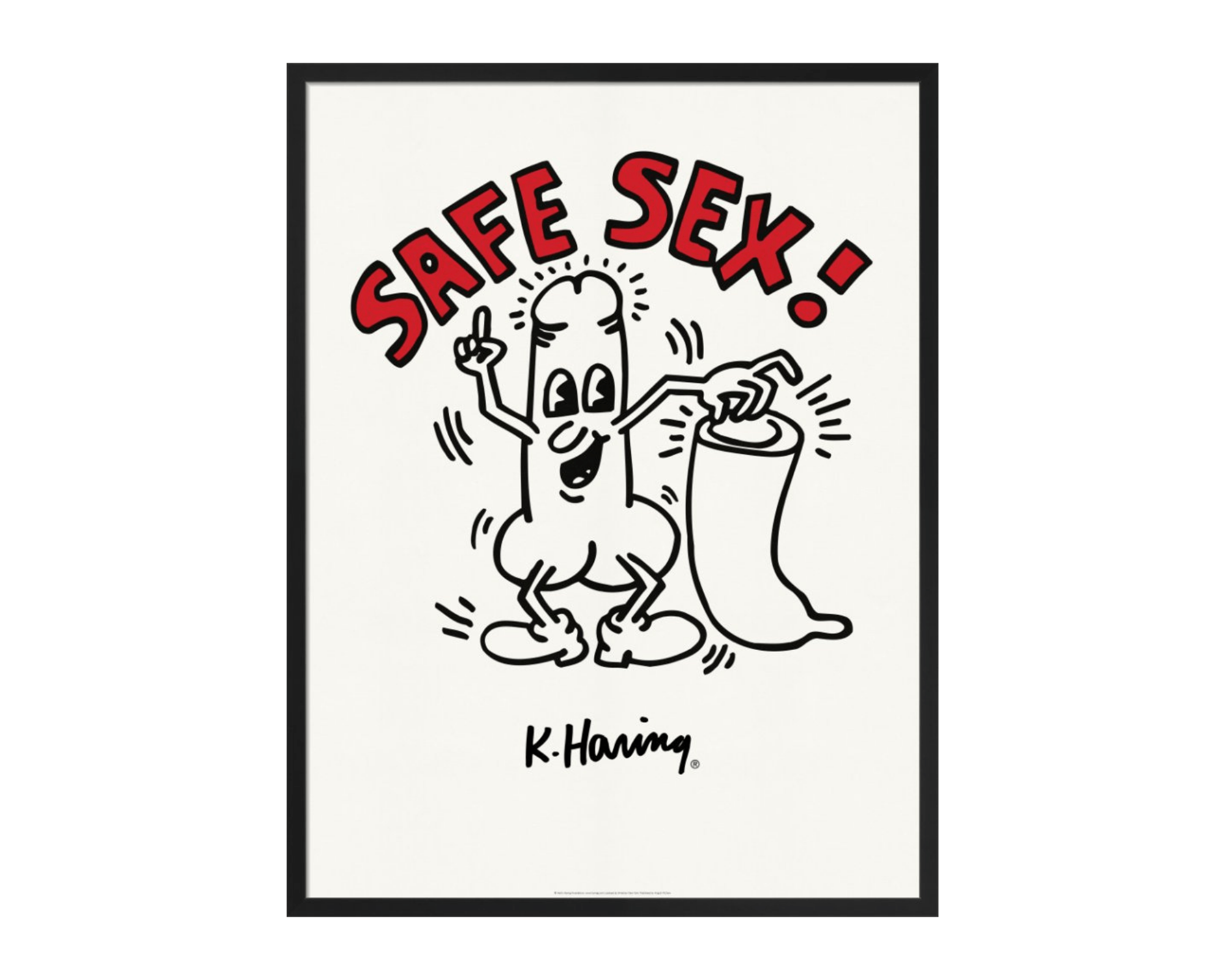

Openly gay and working during the height of the sexual revolution in New York, Haring also felt compelled to speak out about the AIDs epidemic that gripped the city. Building awareness about the deadly disease he himself contracted, Haring tried to combat it with condom case designs and posters that promoted safe sex.

In 1990, aged 31, Haring died of AIDS-related complications. Although his artistic career spanned just twelve short years, he had a major impact on the LGBTQ+ community. In 2014, he was one of the inaugural honourees in the Rainbow Honor Walk in San Francisco, a walk of fame celebrating LGBTQ people who have ‘made significant contributions in their fields.’ Likewise, in 2019, Haring was one of the inaugural 50 American ‘pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes’ inducted on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor within the Stonewall National Monument in New York City’s Stonewall Inn.

We’re honoured to work with Artestar who, along with the Keith Haring Foundation in New York, have given us licence to produce 20 accredited designs of Keith Haring’s iconic posters.