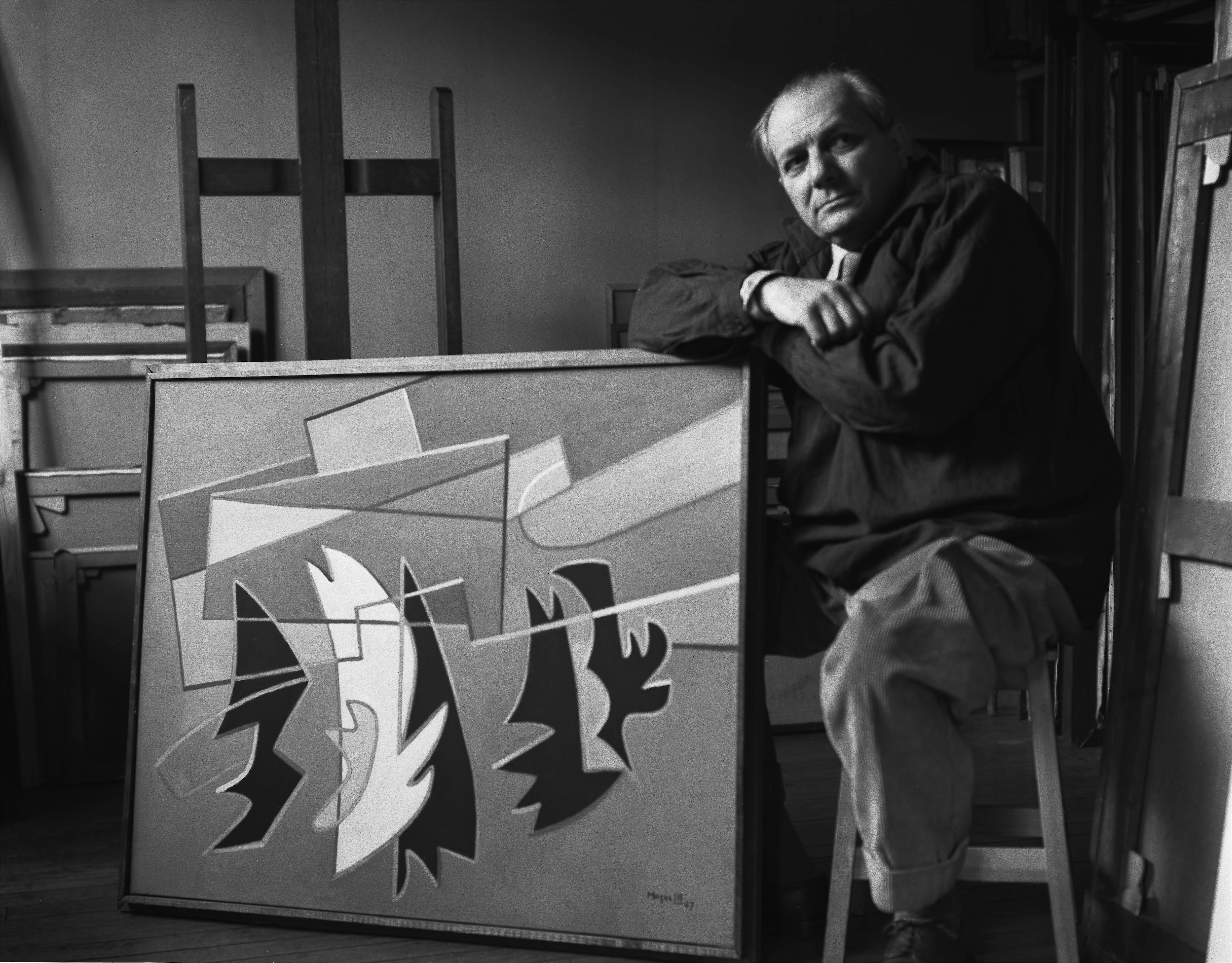

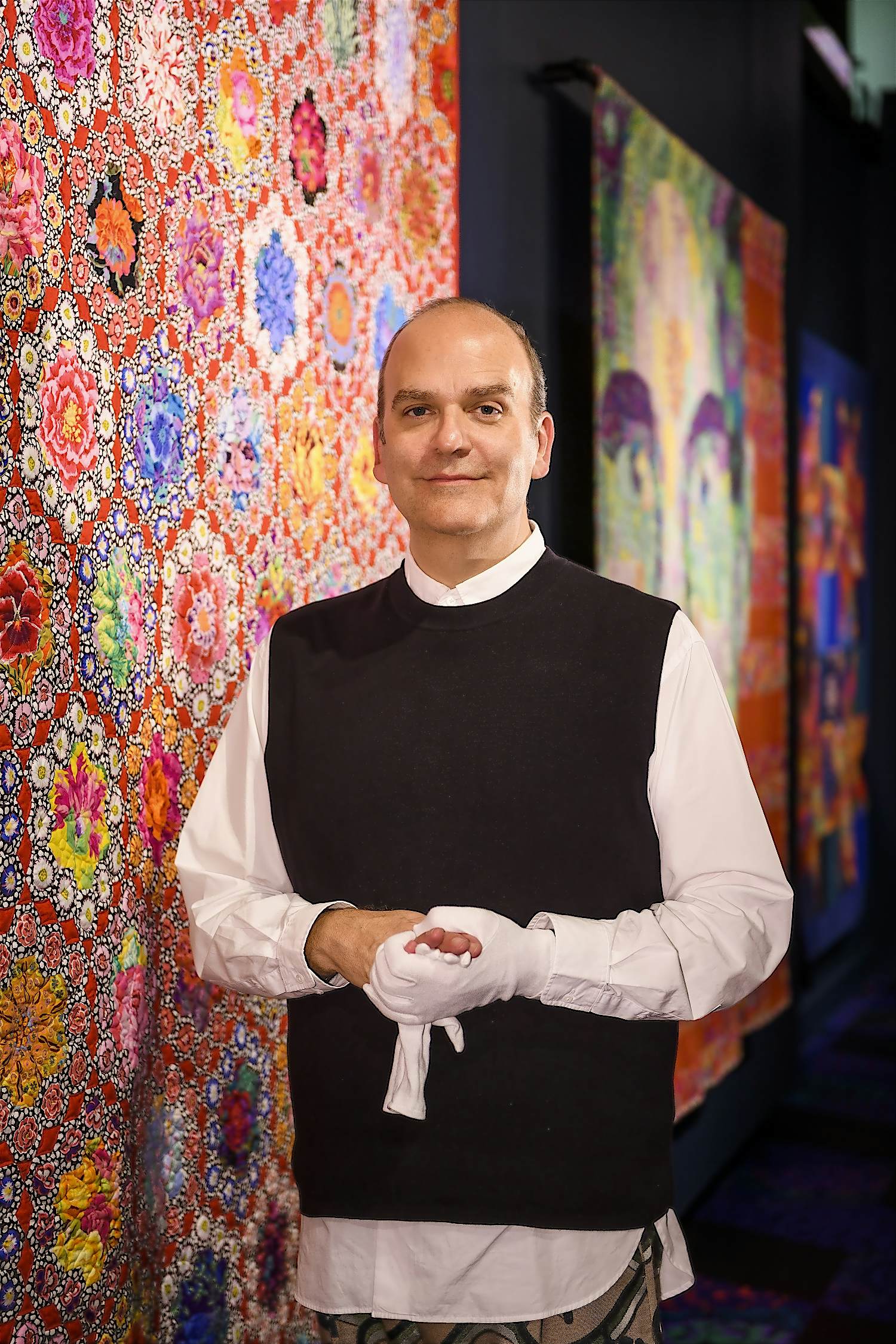

Meet painter and printmaker Tom Hammick, as he sits down with our Founder Gyr King in his South East London studio

Reading time: 11 mins

To mark the release of our collection of Tom Hammick limited fine art prints, our Founder Gyr King visited the artist to discuss how the fragility of nature, the opera, and poetry serve to influence his paintings and woodcut prints, as well as the dark, romantic aesthetic that makes the work distinctly Tom’s.

Gyr.

Hi Tom, it’s lovely to be in the studio and for you to share some experiences, and actually seeing it physically, which is brilliant. I guess the starting point for me is the fact, as we were talking about earlier, that your work has a lot of narrative in it. But there’s a lot under the surface which is coming out of your mind. Do you want to explain that to us a bit?

Tom.

I think there’s a hierarchy in the arts, where poetry is up the top, and you’ve got music, and then about fourth or fifth place down is painting. And if I’m connecting that to the tingle factor, and what makes the hairs on the back of one’s neck stand up, I suppose for me, like a poem I want to work with narrative, but the narrative is often very private.

I was actually reading something yesterday that Tarkovsky said that, why would anyone, why would any artist or filmmaker ever tell them about what was going on, what the meaning of the work was about. But I suppose with me, I’m quite happy to somehow explain some of the narrative points that get me going on an image, without getting into too much detail.

‘I’m doing this weird thing where I’m making pictures that are often seen as quite romantic. But actually, they’re quite dark’

And I suppose it’s important to try and be a barometer of one’s time. And I’m doing this weird thing where I’m making pictures that are often seen as quite romantic. But actually, they’re quite dark I think, in some ways, rather like Caspar David Friedrich had that sort of edge to his work. Or anyone who’s dealing with the way that nature and the natural environment is under such threat.

For me another is a Susan Derges photograph, or even a large painting by Kiefer. So much work at the moment seems to be wrapped up in how fragile everything is around us. And this is partly a narrative that’s behind my pictures. And it partly comes from music and opera, and poems – a lot from poems, and also, things in life. I mean, I go around with a pocket book on the hoof and drawing and I suppose, all that stuff about love and loss and living life goes into the work.

Gyr.

And sometimes that relationship between what you’re expressing as an artist and what the viewer is receiving from an artist, is in different formats. So if you went to Piero Manzoni, who for me, is probably one of the greatest conceptual artists, to write a manifesto, lots of conceptual artists feel the need to talk a lot about their work or to have it interpreted into a lifestyle.

Howard Hodgkin famously did it through titles, and Howard would often say that, ‘the title is all I want to say about the painting and the rest you need to get yourself’. Do you want the viewer to interpret your work in exactly the way that you want it to be interpreted, or do you want to leave it as an open question?

Tom.

It's a great question. And it's one of the key questions, I think.

I bought a Hodgkin early on – I collect when I can, and then you’re broke living in penury, and you have to sell what you’ve collected – but I bought an early print, which I love of his, called ‘Mick’s room’. And what the title conjures up so much, or I don’t know ‘Night in Venice’, or, you know, you get a sexy picture almost looking like a Hopper through some windows, and there might be some bedcovers around, and it’s hot.

But on the whole, with Hodgkin, there’s that lovely title of his called ‘After Degas’, and it's just that beautiful green that Degas uses on this swirling, undulating shape and almost like a paler spring green.

I can taste it, I can link it to Degas, and he might be completely pulling the wool over my eyes and playing games, but he’s not, there’s an integrity there and truth there, and he builds up a picture but it’s my picture. And I suppose I want to do that too, so my titles are very important, and they’re quite oblique sometimes.

Gyr.

And that’s interesting, the analogy with Hodgkin because Howard famously took two or three years to finish paintings sometimes, and that painting would evolve and change as his thought process interacted with it. But thinking about your printmaking for example, they are printed over a very long period of time, do you find your view of them changing? Are you changing, evolving that as you go along, rather than starting with a concept for finish?

Tom.

Another lovely question. I think what you want to do, what I want to do as a painter, and a person who makes prints, or a printmaker, is you get to a point where the picture you’re doing, whether it’s a painting, or a print, or a drawing, starts telling you what to do. And then you’re away.

So I have an image in my head. The thing about printmaking is that it’s back to front, and it’s upside down compositionally, or inside out. So already you’re on the seat of your pants, because you don’t know really how, unless you’re very analytical, like perhaps Hamilton would have been in the way he made his prints, or Patrick Caulfield, I don’t know, I would have thought things were much more planned out early on.

What I quite like doing is, I’m a slovenly printmaker as a painter, I’m not very good at technique so it’s a bit, you kind of throw everything at it. And I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I have a very strong image in my head, and I have a sort of taste in my mouth, and a feeling, a very strong feeling, and the picture has got to try and stand up to that.

‘If I do a drawing, it’s like branding a memory on my brain and I can look at the drawing, it takes me back to the place, even if it’s 15 years before, with the smell and the wind and how I felt that day.’

Drawing helps. If I do a drawing, it’s like branding a memory on my brain and I can look at the drawing, it takes me back to the place, even if it’s 15 years before, with the smell and the wind and how I felt that day. And that might feed into a picture. And I suppose what I’m trying to do is I’m trying to conjure up an equivalent – that sounds very grand, and I don’t mean it to be grand – but I’m trying to aim high, and conjure up an equivalent of… I try to make work about what it’s like to be human really, at the very root.

Gyr.

And that’s an interesting process, because I think the world is divided into artists who are very specific about the print, and it’s very clean, and it’s organised, and it’s technical. And artists, such as Warhol for example, who actually allowed the process to evolve. And I think looking at your prints, there is that interaction between the process and what you’re doing to alter that process.

And sometimes the process can actually demand it goes in its own direction, and that sort of serendipitous aspect of it is quite interesting. And you seem to be somebody who sometimes goes with that, and accepts it. And sometimes fights, almost tries to stop the flow of water coming out of the dam.

Tom.

For sure. I love it when, well no I don’t love it actually, that’s just rubbish. I get very challenged by something that’s not working for a very long time, and often I have to try and sleep. And that sort of state of hypnagogia, where you’re coming out of deep sleep and you’re half in your consciousness and half in your subconscious often helps me resolve something that’s not working. And I try and go with the picture a lot of time, but in the end, if it’s not working, and it’s not working, and it’s not working, however lovely it might look, it’s a disaster really and out they go.

Gyr.

So taking these two parts of your practice, painting and printmaking, do you find the process of painting where you’re clearly much more in control, do you find that the process is different because of that?

Tom.

I’m much more in control in one way, but I think it’s very difficult just technically to have an arris – when you’re painting and you have a paintbrush, and you have paint and it’s slippy and slidy, it’s very difficult to have an edge that is somehow truthful. Do you butt a colour up against another one? Do you overlap it? Does it stand on its own? How much are you thinking about the colour underneath to create – if you have two bits butted up – to create something else happening underneath, the zip of colour underneath, like often Matisse did, or the abstract expressionist a lot of the time did. How do you create a truth in the mark making that’s going on?

And I think that’s very difficult, that really is a seat of your pants nightmare scenario in the studio where there’s so many variables that it’s sort of quantum and at least with printmaking you’re limited in a, why am I in the 21st century making woodcuts, primarily, and etchings, when I’m often trying to make images about living now, you know, like with bits of kit in them.

Helen Frankenthaler is a really good example, you look at that show in Dulwich Picture Gallery, her prints, and they are sublime! And they’re woodcuts, and they’re painterly, and they’re soft, they’re everything that a woodcut with an arris you carve into isn’t. I suppose that kind of constriction with printmaking helps me burst that. And in painting, I need to paint, I love painting and it’s the best thing because it feeds my print and my print feeds my painting, but it’s very difficult.

Gyr.

So I think that what you’re saying, I mean, it doesn’t matter whether you’re a poet, or a musician, or a painter, or a ceramicist, or a potter, we’re all challenged by technique. Technique, ultimately, is always there, it’s nature’s way of saying, ‘hang on, you can’t do this, because of this’. And that technique, that challenge, we evolve over a lifetime of working, we get better and better and better at that technique.

But interestingly, many, many artists that I’ve spoken to actually recognise that as something which takes them towards simplicity, that they constantly in the end, try to end up with something much simpler than they did. Whether that’s because they’ve felt that the challenge of technique is so complicated, or using that mastery of the technique for example, Lucie Rie, in her recent show in Cambridge, was a good example of how her work got simpler, simpler and simpler. And you feel that sort of tension between technique and what the artist wants to do. Do you think as you evolve you want to explore that simplicity?

Tom.

That’s a good question. Alex Katz is a very good example, and I think this is where style comes into it, too. He reduces and reduces and reduces, and he talks about style a lot. And that’s partly from his advertising background. And I suppose I’m passionate about film. So I think there is definitely a style or a pattern going on in both the prints and the paintings of mine, that if you saw one you’d say, ‘oh, that one perhaps is made by Tom’, I think.

When I started painting many, many years ago, I was quite minimal, and I had to learn how to paint. And I’d gone through a phase of the images and the painting and the prints being very complex. And now actually, believe it or not, apart from this anomaly that we’re working on at the moment, I’m getting simpler again. And I am relieved by that. Because I think economy is so important, and I want to get a sense of place and a feeling of truth in a simpler way as possible. And sometimes, for my sins, I totally over egg it.

Gyr.

Klee famously talked about, ‘a painting wasn’t really a painting until it had been subjected to a viewer’, and I wanted to just finish by saying that you’ve curated exhibitions as well. And the one that I particularly remember is the one that you did with Towner, it was an extraordinary vision of some very good artists. I think artists curating exhibitions is particularly interesting, because it’s almost an extension of their practice. And I was very conscious of that journey that you took through, which is exploring the night. And I just thought it was very interesting that you did that. Is that something that you found as a sort of artistic outlet for you? Or was it an anomaly or something that you want to do more of?

Tom.

I’m trying to do more of it. I love doing it. And I think that as an artist, I’ve always looked over my shoulder, and I read art history first. I think, you know, my mum and dad at the time, I always wanted to be a painter, but they said, ‘Come on darling. You need a proper job at some point!’

I read art history at Manchester, and I loved it. But I always wanted to talk to a real artist and I was taught by this wonderful guy called Andrew Causey. He was talking about Lanyon. I said, ‘Can’t we have someone who’s influenced by Lanyon or something?’, (who had died in a glider crash in Taunton a few years before) and I was always saying I want to listen to a real artist talking about how he or she makes their work. And he said ‘Don’t be so silly, we need some distance’. But I think as an artist, I go around looking at things all the time. And I see things all the time, and I’m stealing all the time. And I have my heroes talking to me, as I get older, less so.

I met Prunella Clough just before she died. Angela Flowers had bought a picture of hers and mine and she had this dinner party every year for the people that she bought from. I sat next to her and she was one of my heroes, I adored her work, and I said something very gauche. I said, ‘Prunella, I love your work’ – and I was very young – ‘who are you kind of looking at, at the moment?’ And she said, ‘Oh don’t be so stupid, I’m far too old to be looking at anyone else. I’ve got my own stuff going on’.

But I still look at other people all the time, and that show was a very good example. I was trying to basically get Rosenbloom’s idea of the Northern romantic tradition and I was looking at how Munch and other Scandinavian artists were influenced by people like Turner and Samuel Palmer in this country, and Blake, and then that vision went all the way over to Pinkham Ryder, and Marsden Hartley, and then Milton Avery in America. And I suppose I was using it to try and bind together both sides of what’s happening on either side of the pond.

Gyr.

It was really interesting, and one last thing that you touched upon, which is that I think one of the things that you’ve achieved, which is difficult to achieve, is that when you look at one of your works, you think that’s a Tom Hammick. And I think that recognisable style is something that comes through both the prints and painting. And I think perhaps, it’s one of the most difficult things in a way to achieve in a world that is so full of imagery and information, that to be able to distil something down so your mind and your thoughts are living out there in your works and it’s recognisable and in a kind of way, it’s quite a responsibility.

Tom.

That’s so nice of you to say, that’s really lovely. I always said to my students that they need to draw. And when you’re drawing, you’re naturally editing, you know, a camera will look at everything with one lens, and it will treat everything in the same way. And when we’re drawing if I’m drawing you, my eyes looking all over you, and I’m pushing and pulling, and I’m cutting things out as much as I’m putting things in.

And it’s a natural sort of way of getting to the essence of something and often you need to have an idea before you start drawing, what am I going to do in this drawing? Thank God drawing is coming back, like painting’s come back. But still it requires years and years and years and years of practice, and I’ve drawn every day, all my life. And I think that gives me a chance.

Gyr.

Hockney used to say that all passport photographs should be paintings, because a portrait painting is the person in the whole, in 360 degrees, whereas a photograph is just a moment in time. Yeah, there’s a good point to finish on. Thank you.

Tom.

Tarkovsky talks about that. That suddenly, for the first time ever, being a filmmaker, you can play with time. But that’s the big subject.

Gyr.

Thank you so much. Thanks Tom.

Tom.

Thank you. That was really fun.